Saba Kidane - A Poet’s Upbringing

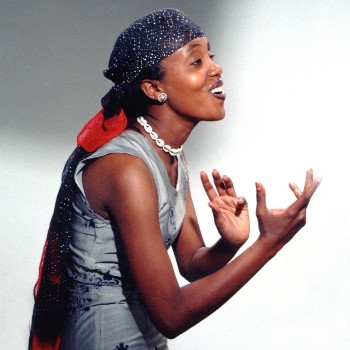

Saba Kidane, a poet, performer and journalist, does not only recite her poems elegantly but she manages to sketch what she saw and experienced in post-independence Eritrea with exuberant confidence and passion. The savoir-faire and street-wise poet, now based in Paris, is a powerful chronicler of the misery of urban life who ‘sees children growing older, boys and girls flirting and poor women begging in Asmara’s streets as autonomous poetic subjects[1]’.

Saba Kidane, a poet, performer and journalist, does not only recite her poems elegantly but she manages to sketch what she saw and experienced in post-independence Eritrea with exuberant confidence and passion. The savoir-faire and street-wise poet, now based in Paris, is a powerful chronicler of the misery of urban life who ‘sees children growing older, boys and girls flirting and poor women begging in Asmara’s streets as autonomous poetic subjects[1]’.

Saba readily acknowledges the shaping influence that her old neighbourhood and her mother had on her life and work. When asked about her childhood, she said:

I was born in the heart of Asmara during the Dergue era. I grew up in a neighbourhood that propped up its back on Abashawul, facing Edaga Hamus. Godena Ra'esi BeraKi BeKit, as it was called then, is what comes to mind when I think of my childhood. Basically, I was born in house-number 62 and raised in house-number 26.

Saba is such a good story teller she mesmerizes her listeners as she flirts with her lexis. When her mind drifts back to the good old days of her youth, as she conquered the streets of her rough neighbourhood, she immerses her audience in every aspect of her being. In other words, her recollections are so vivid she can literally take one by the hand and lead him through the crowded streets of her old locality. Saba can talk for hours about the time she spent at her aunt’s and uncle’s places when her mother went to work, playing around the bar t’Um zeben, the centre of activities in her neighbourhood, visiting her first school at enda’boy-qeshi (enda Selassi), where she learned how to recite prayers in ge’ez, running errands for her mother to the small kiosks and street vendors … stories that still remain engraved in her mind. Most of all, Saba remembers her visits to adey Ribqa’s place - a prominent and rich woman who lived in house number 114. ‘In fact, Adey Ribqa’s place was my first library’, says Saba. That was a place where she could find discarded old newspaper clippings which she read thoroughly and obsessively.

One person in particular captivates Saba’s imagination - her beloved mother who passed away one year ago. One can say that many a times her mother still dwells in her deepest memories, and probably is the source of her most intimate poems. She remembers her mother's prayers well, and she believes they have always been following her. Saba can describe, in her unique ways, how her mother used to sit in front of the Qonanit during the hair-braiding rite conducted at home. She can also weave a wonderful story around special occasions – how she used to apply Henna or Illam on her mother’s hands and feet – colouring tints that leave durable stain on the outer layer of the skin.

Where does Saba’s love of writing poetry come from? ‘My poems come from ordinary experiences and objects, I think’, she said. ‘Many come out of memory’, she added. In her conversation she casually mentions the very first book she read about ‘Beauty and the Beast’ in Amharic, a story that left a lasting impression on her. She remembers newspaper stories and photographs, the neighbourhood fights that kept her constantly on her toes, the leaky roof of her small dwelling, the time she attended secondary school with her baby straddling her waist, her Beha’i faith that still keeps her honest to herself, Memhr Tekle Tekeste, one of her favourite poets who, sadly, committed suicide 13 years ago … all touching her heart and soul with a gesture of love.

Saba’s work, for the first time, was digitally published by Asmarino.com in 2001. That was during the time when Eritrea was experimenting with free press. She was highly regarded then for her realistic depictions of family life in post-independence Eritrea. And many remember her command of the formal and colloquial aspects of Asmarino parlance, so to speak. A star was born alongside that of the late Russom Haile, Eritrea's first internationally known poet. But then she disappeared from the poetry scene all of a sudden. Perhaps she became the victim of her own success. Apparently, the regime could not stomach individuals like her who rose to fame without 'government permission' or out of government control. To explain her sudden disappearance, she said: 'what transpired in the Eritrean political and social landscapes came as a total shock to me'. 'For life to become real life it needs all the natural components in its orbit to revolve around it smoothly', she added. The chaos that erupted then - imprisonment, harassment, bullying and muzzling - put her off her stride. That, in turn, created a vacuum in her. Saba re-echoed the sentiment by saying:

Saba’s work, for the first time, was digitally published by Asmarino.com in 2001. That was during the time when Eritrea was experimenting with free press. She was highly regarded then for her realistic depictions of family life in post-independence Eritrea. And many remember her command of the formal and colloquial aspects of Asmarino parlance, so to speak. A star was born alongside that of the late Russom Haile, Eritrea's first internationally known poet. But then she disappeared from the poetry scene all of a sudden. Perhaps she became the victim of her own success. Apparently, the regime could not stomach individuals like her who rose to fame without 'government permission' or out of government control. To explain her sudden disappearance, she said: 'what transpired in the Eritrean political and social landscapes came as a total shock to me'. 'For life to become real life it needs all the natural components in its orbit to revolve around it smoothly', she added. The chaos that erupted then - imprisonment, harassment, bullying and muzzling - put her off her stride. That, in turn, created a vacuum in her. Saba re-echoed the sentiment by saying:

Over the years I became that incomplete Saba as many things in my life fell apart. People went missing one by one and the constellation of artists and writers vanished right from under my nose. You see, to do anything in our culture one needs a group of companions - we do not do things alone. One needs someone to eat with; one feels more comfortable when surrounded by friends and family; one needs a literary companion to work with. That disappeared from my world.

What is unique about Saba is the fact she gets lost in her poetry when reciting. Poetry is her real world now, as far as she is concerned. The eruption of her imagination and poignant poetry, when she shifts her passion, with the energy of desperation, from the child she was, the woman she is onto the world of poetry, dominates her discussions. The chaotic reality of life in Eritrea is always present on her mind.

The state of ‘peace’ in Eritrea has become a costly affair; and Saba, without flinching, continues to tell the story how that very ‘peace’ affected her and her children. And yet she manages to maintain that maternal bond with her children as she remains calm in the face of adversity … the children hold on to their mother as she continues to sacrifice her feelings for ‘peace’.

After going through four rings of fire, Saba does not condemn herself but continues to celebrate her upbringing; she sees her post-childhood domicile, her current state as another challenge, another way of fighting, another cause.

[1] Charles Cantalupo (2009): War and Peace in Contemporary Eritrean Poetry; Mkuki na Nyota Publishers Ltd, Dar es Sallam.

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)