A Book Review - ለኸን ኣኽራ መርወዲ (The Ring which Became a Sore)

A Book Review

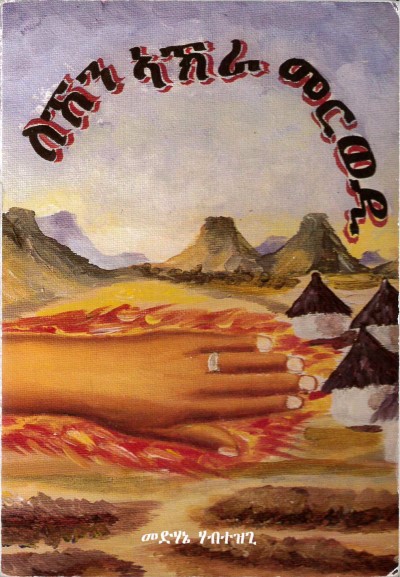

Medhanie Habtezghi (2008). ለኸን ኣኽራ መርወዲ (The Ring that Inflicted Pain, or literally, The Ring which Became a Sore[1]), AIT e-dit, Oslo, Norway18 chapters, 166 pages, Introduction, Acknowledgement.

Summary and Review by Kiflemariam Hamde,

Umeå University,

Sweden

The purpose of this review is to present Medhanie’s first novel work titled Lekhen akhra merwedi (A Ring that Inflicted Pain) for the sake of a wider audience especially those who are non-Blin speakers and those who cannot read Geezword. My aim is to point out the main story line and also to appreciate the author for his original literary work, which I can consider to be the first ever Blin literary work in this genre (novel) in modern times by an original speaker. I think critiquing the current literature through literary theory is out of question due to three reasons: first, I am a scholar in Organizational and Managerial Studies, not a literary theorist and thus it is not justifiable to do so at this moment; second, my aim is rather to show that Blin literary work is on the rising since the mid-1970s and for that a sound summary might be more relevant. Third, as far as this reviewer is aware of, there had not been any novel work written by a Blina (i.e., Blin speaker) of such high quality as it has not precedent to which one can compare the quality and development novel work in Blin. The originality of the current work thus makes it standing out independently even if there have been poetic works[2], fables and tales which anyway belong other literary genre. In this summary, if there is anything that tends be inconsistent with the original argument or just not sufficiently focused on, I remind readers to put their reading in that context. If there are any mistakes or omissions in this summary, it is only because of the reviewer’s preference for selecting a particular story – focusing on the two main characters, and not because lack in and of sufficient material in the book.

The purpose of this review is to present Medhanie’s first novel work titled Lekhen akhra merwedi (A Ring that Inflicted Pain) for the sake of a wider audience especially those who are non-Blin speakers and those who cannot read Geezword. My aim is to point out the main story line and also to appreciate the author for his original literary work, which I can consider to be the first ever Blin literary work in this genre (novel) in modern times by an original speaker. I think critiquing the current literature through literary theory is out of question due to three reasons: first, I am a scholar in Organizational and Managerial Studies, not a literary theorist and thus it is not justifiable to do so at this moment; second, my aim is rather to show that Blin literary work is on the rising since the mid-1970s and for that a sound summary might be more relevant. Third, as far as this reviewer is aware of, there had not been any novel work written by a Blina (i.e., Blin speaker) of such high quality as it has not precedent to which one can compare the quality and development novel work in Blin. The originality of the current work thus makes it standing out independently even if there have been poetic works[2], fables and tales which anyway belong other literary genre. In this summary, if there is anything that tends be inconsistent with the original argument or just not sufficiently focused on, I remind readers to put their reading in that context. If there are any mistakes or omissions in this summary, it is only because of the reviewer’s preference for selecting a particular story – focusing on the two main characters, and not because lack in and of sufficient material in the book.

In ለኸን ኣኽራ መርወዲ (A Ring that Inflicted Pain), the author starts off the 18 section novel about the fate, upbringing, love, and final destination of two Asmarite young lovers, Rahel and her friend Milkias. The scene was conducted between 1980s to early 1990s, starting in Asmara via Keren and to the Sudanese border, until the two were captured by the EPLF squad and forced to join the fight for liberation in Sahel in spite of their destination was to escape from home and live fully their love somewhere else. Finally, one of them returned safely to Asmara in 1991 with the independence of Eritrea. The other partner could not come back home after independence. What happened? How did they live their love before and after they joined the EPLF, and what were the consequences for those who were involved in their relationship or love affairs and their friends? The author provides answers to the questions, adding spice to the staff in the story. He takes the reader all the way from Asmara to Keren, the escape to the Sudan and finally, the surviving partner ending up getting wed with his lover’s friend who lived in Keren. You might wonder where the picture of the Ring that became a Sore comes into this picture in the narration. The Asmara-born Rahel who in her summer vacations used to stay with her grandmother in Keren befriended Lidetu and the ring was given to her as a sign of their friendship. The question then becomes “pain to whom, when and how”. It is a story of how the result of a ring offered by a young Asmarite lady to her female friend in Keren eventually could become unbearable to the latter. Was the sore healed or did the beneficiary of the ring suffered for life? What happended to the ring giver (Rahel), to Milkias, and to Lidetu? Enjoy reading to synopsis of the story, or if you are a Blin speaker, you can just stop at this point and read the whole book instead; it might add to your entertainment during your leisure time, or during training others how to read and understand Blin literature.

In the introductory chapter of the book, the author starts off by reiterating the ensuing peoples’ joy and disillusionment for the independence of Eritrea after May 24th 1991when they celebrated for three months without interruption. It was a period of unending ululations, dances, and optimism. Eventually, the people had to encounter the reality that it was only some families who rejoiced by the arrival of their sons and daughters from the war while some other families were saddened and surprised to see that their beloved ones did not yet come home. What happened to them? Did they get martyred? Or were they still somewhere in different parts of the country such as Denkalia, Sahel, or inside Ethiopia? No one knew, and this added more worry, uncertainty, confusion and pessimism. What was more disturbing was that both the returnees and the EPLF cadres were forbidden to tell the truth about who got martyred or who survived. Consequently, people faced a dilemma as whether to continue enjoying the success of independence or just wait if their beloved ones could arrive safely someday – “to suffer unknowingly”. The author describes that it was better to “choose the bad to the worst” (chegem chegemsi sabisgini) to explain that it was better to know if your beloved had been martyred than living in a limbo (p. 2). The author then recounts that a year after, in June 1992, the Provisional Government announced the list of 65000 martyred during the 30-year war for independence. Although families were informed about those who were martyred, argues the author, it was an end to the long waiting period even if it was finally to lose their last hope of meeting their children again.

Amidst all those events, the author recounts as Reka listens quietly this interesting story. Early on in the morning of the 28th September 1992, Reka travelled from his residence towards the site of Meskel (መሰቀል) feast celebration at the Keren Football Plane (juoko) and alternated the Blin folk songs and dancing among five dancing stations where youngsters from the villages of Bogus, Sekwina, Qunie, Megarih and Wesbensrexw conducted their annual Meskel celebrations while the ever Blin enthusiastic girls played the drums. After visiting and dancing in these Meskel (መሰቀል) celebration, Reka was exhausted and wanted to get a rest in one of Keren town refreshment cafés and headed towards Jira Fiori (Flower Square) towards the center. On his way, Reka met a primary school mate, Lidetu. She was going home towards Shifshifit after weekly shopping; as the chatted, Lidetu invited and persuaded Reka to follow her home. He did, and after chatting about their school time memories and commented on the behavior of some teachers and students. Reka told Lidetu he also lost on of his brothers in the war. Then, it was time for him to visit the men’s room. To his surprise, upon his return, Reka found her in a bad mood, as she had lost her temper. She simply kept weeping in tears without interruption. Reka thought that he caused some uncomfortable expressions unconsciously. But that was not the case. Lidetu tried to convince Reka that it was due to the loss of Reka’s brother who was martyred in the liberation war. Reka was not convinced and rightly, because he was quite sure that Lidetu had never ever met his brother and even then, that was not a sufficient reason to weep so much. “Liday”, exclaimed Reka changing her name in a positive parlance, “that is the price we Eritreans paid for our independence, and we have accepted that” (geninxun, p. 6). Eventually, Lidetu started telling Reka the real reason for her sorrow. “I wish to have avoided getting that ring which became a sore and that caused me all of the tears and sorrow in my deeper self. I could not get anybody who could comfort me from that sore that incurred to me from this ring”, continued Lidetu (p. 6). Surprised and uncertain as what to say and how at the same time comfort her, Reka tried to persuade Lidetu that one cannot weep just for a ring. “That is only a thing, you know, and it is not reasonable that you could also be weeping because you possess a golden metal. Be happy, intead” (p. 8). Moreover, Lidetu hid this deeper secret or a value that could not leave her in tranquility and peace of mind: she did not dare to wear it, sell it, or even exchange it. It was a dear symbol of friendship. Moreover,

Eventually, Lidetu explained that she got the ring from one of her best female friends, Rahel, when she departed to the Sudan with her boyfriend, Milkias. The ring was a sign and a symbol of their permanent friendship. Even if Rahel and Milkias headed towards the Sudan, they never reached Sudan. The question of why they fled from Asmara, why they did not get to the Sudan, and why only Milkias returned safely home after the liberation of Eritrea in 1991 turns out to be a love story between Rahel and Milkias. To save her love, Rahel decided to take all the possible risks on her way, at times crossing both mental and physical boundaries. Lidetu narrated to Reka the whole story from the very beginning in 1980s when Rahel and Milkias were school mates, friends, and up until 1992 when she was confronted by Reka to know everything about “Rahel and about “The Ring that Became a Sore”. Reka’s role ends there while Lidetu played a crucial role in facilitating the journey from Keren town towards their destination to Sudan.

Rahel was born and raised in Asmara in the Gajiret area. Her family were well to do, her father Mieron was a physician who got his education in an Ethiopian University and worked at the Mekanehiwot Hospital in Asmara. However, he met Rahel’s mother Jewdi in Keren when the former was practicing his first job in Keren hospital, got married legally and begot five children. Jewdi was 12th grade student when she met the physician Mieron. Firstborn (bexri) Rahel, was born after waiting for nine years, was naturally liked and well taken care for by the whole family.

Blin speaking Jewdi’s family lived in Keren, especially Hidega, Jewdi’s mother lived alone in a big compound, and Rahel used to stay with her during summer vacation. Furthermore, Rahel’s family belonged to the respected nobility – enda Dajazmatch. They were one of the middle classes in Asmara. As Rahel grew up becoming beautiful with soft and strong body, light colored, boys in her surroundings offered their invitations to befriend her. As many well-to-do families at that time, in the 1980s, Rahel first attended a Private School, Emanuel Primary School at Gajiret, and eventually joined the Barka Secondary school. It was during that time she fell in love with one of her classmates, Milkias. Originally, Milkias’ father immigrated from Tigray to Meraguz in Seraye, and as he worked in the farm, he befriended his employer’s daughter, Yeshu. He was bound by customary law to marry her and eventually Milkias was both followed by five others. , and after they got married, they moved to Asmara. Milkias family thus has mixed background, his father coming from Tigray and his mother from Seraye in Eritrea. Furthermore, Milkias aunt (Yeshu’s sister) lived in Keren in a residence called Gezawereqet. where many immigrants from Tigray and Eritrean Highlands settled and sold different local produces including the local beer (slkh) and mead (mies). She also was one them. Yet, until a later time Milkias had never visited Keren, and by the time he did so, we will soon learn why.

Jewdi, Rahel’s mother enjoyed entertaining in a coffee ceremony with her daughter as her husband was often late at his work. Once in their coffee session, Rahel dared to explain her affairs with Milkias to her mom that she was in love with a classmate, and her mom did not object because “supported her in her schoolwork”. Her mother simply believed her. Gradually, Rahel explained to mother Jewdi that she actually fell in love with her classmate who helped her in all subjects, and it was due to that she scored quite well in her subjects, especially Math’s, Chemistry, and Physics. Her mother became fond of meeting him (may be jealous) and when she did meet him, she liked Milkias. The truth however was the reverse. Rahel was clever enough to pass with great distinction without the support of anybody. Every summer vacation, Rahel stayed in Keren with her grandma who renamed her as Dinsa for her beauty. Her grandma lived alone on a big compound. But Rahel missed Milkias painfully during summer vacations. Once she cheated her parents and took with her sweetheart, Milkias. Not only that. She paid the bus ticket, gave him pocket money, and convinced him to follow her to Keren in a different date, pretending that he went there to visit his aunt in Gezawereqet. Rahel asked her grandma for a corresponding male to name as she liked being called Dinsa. It was meant for her lover. Her grandmother suggested many names but it was Sheru that Rahel chose for Milkias, thereafter his name became Sheru in their informal chats – Dinsa and Sheru, instead of Rahel and Milkias. Gradually, Rahel cheated her grandmother that she wanted to meet her friend (meqela, a female friend) and were out several times with Milkias. Moreover, Rahel was still unsatisfied. She wanted her Milkias on her side even during the night. When her grandma went to bed early evenings, Rahel smuggled Milkias very carefully and thus they used to live together at night, in the same bed, and enjoy their love from alpha to omega until they got separated early mornings when her grandma went to church. Her grandma knew nothing about all these. After all, her family members had a deep trust in Rahel – they believed that in fact she was clever, careful, and somebody who looked for her future development, and she could never fall into risks about her own virginity – not to bring any shame to herself and disgrace to her family. “Rahel could never risk losing her virginity”, thought at least her mother. When Rahel explained mother about Milkias, Rahel easily convinced her mom that nothing could change in her manners and behavior. It was only a relationship.

In the meantime, Rahel did everything that a loving partner could do to keep their love. She never asked Milkias where he came from or if his family had a different background than hers. That was not important for her. When his wife Jewdi explained about the relationship, father Mieron was serious enough to challenge both his wife and his daughter to not get married to unknown people, people from the South of Eritrea, meaning Tigray, with whom his family had no relationship at all. In all his extended family, and that he comes from middle class family made it unfitting to have any relationship with a poor, hand-to-mouth family. Additionally, Milkias father also was known for being a drunkard even if he had a workshop at Medeber. Learning about this and also challenging his daughter that the idea is not only wrong but would also lead to family defamation, humbling of their own class and traditional values. Mieron asked his daughter to stop the relationship immediately, never meet that poor boy. Mieron, the proud and rich father warned her if she continues the relationship, Rahel could be expelled from home. “Expelled from home”, pondered Rahel? And she decided to take all possible risks to save the relationship. Especially worrying for Rahel was the fact that contrary to her will, her father unregistered Rahel from Barka Secondary School and instead she would continue her studies in Santa Anna Secondary School, “so that, he thought, “Rahel could never meet that poor boy”. But Rahel was determined to save their love affairs at any cost, regardless of the hazards on the way! Rahel never thought of continuing studies in the new suggested Secondary school nor did she want to stay in Asmara. Milkias, although hesitant at times, just nodded. Her suggestion to Milkias was to escape home and travel to Sudan via Keren, and that the good Lidetu would facilitate the arrangement. “It is better to disappear from this conservative family than being expelled from home”, she thought. What mattered most was being with Milkias. Of course Milkias was also disappointed by the conservative attitude of her father even if at the beginning Rahel’s mom had good intentions about him. He could not afford the feeling of being rejected, disgraced and shamed only because he came from a different family, he felt how painful it was to be considered as alien, the Other. He also observed how Rachel’s’ mother, Jewdi, changed her mind because she was afraid of her dear and well-to-do husband and thus she could not protect her daughter. On the other hand, he daughter also lied to her pretending that she never had sexual relationship (sxi werat) with Milkias while “everything was consumed while they stayed in Keren during the previous summer’, maintains the author in nicely crafted words.

Rahel felt that lif eat homewould be untenable and decided to escape to the Sudan together with her boyfriend Milkias. To do that, she had to once again cheat her parents pretending that she would visit her grandmother Hidega in Keren. The ever friendly Rahel’s fined, Lidetu, facilitated and arranged the contact with a Juffa man called Gamil who could smuggle them out of Keren town via Shifshfit towards the border of the Sudan. Gamil planned to take them during the night and smuggle them out of Keren town via Shifshfit and Juffa, down to Boggu (Enkmteri), and on their way to the border of Sudan; they passed Inchinaq, Barka River, etc. It is amazing how the author details the route towards the border in time and place. The author’s knowledge of the places is amazing, and as a reader one ponders if he once were taking the same route to a destination. In any case, Rahel and Milkias had to face heavy barriers and at times both mental and physical borders towards their destination to Sudan. As noted above, the first real challenge or barrier was the conservatism of Rahel’s dad, Mieron, who strongly warned his daughter that she could not marry an alien. But the escape to Sudan was to do the trick for them. But could it be a project to embark on even if they got “Gamil who they believed could take care the forest jungles snakes, hyenas and wild animals in that country side which many Asmara children are so afraid of?” Again, another major barrier was how to cross the check point from Keren town towards the country. While the Juffa smuggler could cross the check point during the night, they were both captured by the Ethiopian army who asked Rahel’s body and also wanted them jailed afterwards. Rahel at first pretended to have allowed him her body fully - (Teleqrso beT yti) as is she was cooperating in that bad action! Yet, she had a different plot. - To kill him as he hungrily lay his body on her, throwing his gun far away. She indeed strangled his throat to death in only for three minutes. Sheru (Milkias),

“do the same” (belo) and indeed Sheru followed the suit killing the other solider with a big blow on his neck and then trashing him down to the ground. “What a brevity! Once free from the soldiers, they ran ahead unhindered to Gamil who watched everything from a nearby hiding. They thus won over the second barrier also”. Could the smuggler succeed taking them safely to Sudan?

The third barrier was the problems encountered in the boundary between Eritrea and Sudan. Even if Gamil used to cross the boundary a couple of times before, it was not possible at this time. All three, Rahel, Milkias and Gamil were captured by the liberation army forces who controlled the boundary. Gamil was imprisoned directly because it was his second time coming to this point. But he later escaped, went back to Juffa and continued his ordinary life as a farmer. What happened to Rahel and Milkias? Even if they took all risks to save their love, they were asked to join the liberation army in Sahel, and thus ended up in the liberation war military training. The rest is that history in Sahel together with other EPLF fighters with it sups and downs. As EPLF liberation army members – where they met many Asmara youngsters - Rahel and Milkias did not dislike at all the life of becoming part of freedom fighters. They simply did not think about it or rather they did not know how it looked like. Their only concern previously was ‘living together in love”. However, they were allowed to visit each other during the time vacation in the liberation army (EPLF). They wished to have tried shooting the enemy. They were even jealous for not participating in the demise of Nadew Command in March 17th to 19th in Afábet in 1988. They also wished to have participated in the Battle of Massawa (also known as Operation Fenkil) which took place in February 8, 1990.

Yet, Milkias and Rahel visited each other and stayed together in a camp and thought about their future in the liberation front. “The worst scenario”, maintained Rahel, “could be if only one of us survives!” They considered it to be right for the survived not to love or get married. They both were incited by the idea or scenario if both survive the war. Both dreamt of a life with their families again and at the same both wished meeting Lidetu (but Gamil was not mentioned). Fortunately for Eritreans, recounts the author, Eritrea became Independent in May 24th 1991, and Milkias travelled via Ghinda to Asmara with the victorious liberation which crashed the Ghinda Front (the Right Flank). Rahel was siding with the Left Flank along the Segeneity - Decamare Front, which faced a fierce defense, and consequently, she fell down in the Third Offensive war near Decamare. At this moment, the author takes the reader to the opening festivities and joyous moments immediately after Independence. Even if Rahel did not make it, her name was registered with the winning fighters as a martyr with those who fell down for freedom, and liberty. Yet, it was unbearable for Milkias who in fulfilment for the promise that the survivor would not get married to anybody, he decided to remain unmarried for his all life. It was also a pain for Lidetu who learnt that Rahel’s name was in the list of those 6500 which was read in June 1992! The ring thus became a sore for Lidetu who never dare sell it, wear it, or even exchange it for the like. She felt deep in her heart that doing away with the gift-ring would be betraying he friend Rahel, and also keeping it meant suffering all the time as it was a reminiscent of their relationship. It was simultaneously a dilemmatic and a paradoxical situation for Lidetu.

Since the liberation of Eritrea and realizing that Lidetu would never meet Rahel, Lidetu often thought, if she get married, “to call her child Rahel and give that ring to the newly born daughter in memory of the real Rahel”. In 1994, Milkias went to re-visit his aunt in Keren, and met Lidetu who was on her way from shopping session. They started talking about the inevitable – Rahel, and eventually about the ring that was a painful enough for Lidetu. In their chat, Lidetu asked Milkias if he had any affairs with any lady. Surprised, Milkias responded, “not at all, not after Rahel”. Eventually an idea came to Lidetu if they both could instead get married and name their daughter Rahel. “It is a fantastic idea”, nodded Milkias but he knew how difficult it could be for him, remembering the way Rahel’s parents mistreated him and worked against him in considering him to be alien (gefra-kedenukh); he understood how they also mistreated their own daughter harshly – causing all the turbulence and escape from Asmara, consequently missing Rahel. “This is rather an impossible idea”, Lidetu, Milkias contended. But Lidetu brought a creative idea that solved many of the hesitations and problems. She knew how to draw her parents into a trap so that they cannot refuse her marrying him. She would first become pregnant, and then it was only time for her parents to hasten for a wedding ceremony lest they risk shame and disgrace - “people would rebuke the family that their daughter got a baby before marriage, a curse to many Blin parents”. Lidetu, like Rahel, was not interested about Milkias’ family origins. At last, Lidetu and Milkias initiated affairs and Lidetu became pregnant. As Lidetu predicted, her parents simply rushed for a wedding ceremony to avoid dismay and shame from their community and to pretend that everything was done in the normal way. After all, all got what they wanted. The baby was a girl and they named her Rahel. It was a big relief for Lidetu, joy for Milkias, and also justice for martyr Rahel whose name could live in a loving relationship. It was also relief for Lidetu’s family who could not resist her decision to marry Milkias whom they started considering as a responsible husband to their daughter!

In this new book, the author exhibits great maturity in all aspects – it shows his pragmatic competence and in his use of pragmatic particles of the Blin language. I suggest this book to be relevant and indispensable in literary studies in Eritrea at all levels, and also a good training manual for those who want to develop their skills in Blin writing. Medhanie has filled a badly needed gap in Eritrean literary work in one of the nine Eritrean languages, thus providing us with a milestone in this genre. This original work is well-researched in terms of places and geographic routes in Eritrea, well-thought with eloquently crafted language that did not have precedent (of its kind) in Blin language studies, with metaphors and rhetoric leading to an entertaining read, and at the same time instilling more enthusiasm as what would be following.

ለኸን ኣኽራ መርወዲ (A Ring that Inflicted Pain) is not only a love story but it also includes details during the liberation war period, the liberation hysteria in 1991, and aftermaths, as well as different life situations from the very starting of the actors in Asmara as young students and youth life in the city, and geographic constellations in Keren, Barka and Sahel, finally narrating the final war in May 1991 and it spatial context. The narrative gives a big blow to stereotypes and conservative ideas and highlights the power of love and free will, and at the expense of arranged marriage. If I were to compare the quality of ለኸን ኣኽራ መርወዲ (A Ring which became a Sore) with previous literary novel in Tigrigna, Musa Aron’s Werqha (1966) and ኣምባ ኣፍራሽ (Ambafrash, 1967), together with the work of Yisak Yosief’s (1993) ሕንዛም ፍቅሪ ህድኣት (Hnzam fqri Hidat - Hidat’s Poisonous Love) and ሓደገይና ፍቅሪ ንጽሕቲ (Dangetegna fqri Nizihiti, Nizihiti’s Dangerous Love) come closer as narrative forms. In that sense, Medhanie adds to the growing literary work in Eritrean languages, in conjunction with the 2001 Conference in Asmara against All Odds: African Languages and Literature in the 21st Century, thereby contributing to the vitality of Eritrean languages in the development of literary work.

If one were to evaluate if the author has achieved the purpose of this work as introduced in the Preface (p. i) where he claims to aim at providing readers with an entertaining and simultaneously to developing skills in Blin writing and reading, I can only affirm that he had achieved the purpose quite well. This work is indeed a good novel for all features of the genre. It provides particular, not general type, characters (Reka, Lidetu, Rahel and family, Milkias and family, the EPLF fighters, the Ethiopian soldiers) in specific contexts in time (1980s to 1994) and Place (Asmara, Keren, to the border of Sudan, via Barka, Sahel and then to Ghinda, Decamare, war fronts and liberated areas). Lekhen akhra merwedi (A Ring which became a Sore) shows events in contemporary Eritrean context, and the characters and context are reliable enough (for example the route form Keren to Sudan’s border, and details in the liberated areas), as well as tradition-free language (skhi werat (sexual intercourse where the initiative was often taken by a female character), knfursi selemna (lip-kissing), and rejecting traditional socio-economic stereotypes etc.

The author shows self-consciousness in using innovative terminology (Hunter, 1990, Before novels). The novel shows the author’s great linguistic competence, narrative structure and eloquence, thus succeeding in achieving the formulated aim. As example of his use of innovative terminology, the following new terminology whose meanings are translated into English in brackets can be given. I consider these as substantial and innovative additions to Blin vocabulary. For record, examples include siélires atena (design, Acknowledgement, p. iii), Ertri Ika mahber gbra (formation of the Eritrean community, p. 2), Hanun (Music, p. 13), bHto-yri (private, p. 13), mhror ame (academic year, p. 14), jikhnar (poverty, p. 15), aqshun lwru (subjects, courses, p. 23), reChan (target, p. 37), meeb iyay (class teacher, p. 47), ledot (experience, p. 48), attain (methodology, p. 49), mndae (measure, p. 51), siaseted (systematically, p. 54), dahafat (exaggeration, p. 55), Kwotmay (guardian, p. 63), qwah-sem (second, p. 88), korit seqerukhw (basket all, p. 105), karni mekteb (immigration office, p. 131).

Finally, I recommend readers to taste the beauty in the language, enjoy reading the first overarching text and well researched work, an author from I expect to review his second book, enkie!, for the sake of readers in English, as he translated it already in Tigrigna lekas!. Well-done, Medhanie!

Medhanie Habtezghi, LLM, lives in Oslo, Norway, and is a father of four.

He has earned (1) LLB at the University of Asmara (1999) and wrote a senior thesis “Customary Marriage and Divorce in Blin Society”, and he did his Masterate degree (LLM) in Public International Law (2010) with a thesis titled “Environmental Protection in Eritrea under the Light of Biodiversity Convention and the Rio Declaration Principles: the Interdependence of political, Economic and Environmental Principles”. University of Oslo, Norway.

Medhanie can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

[1] The reviewed work is the first novel based on facts by the same author. It was followed by another title, Enkie, (እንከኤ) translated into Tigrigna as lekas (ለካስ, and in English as a Surprise! It will be reviewed eventually so that readers who do not understand Blin may be able to get more information on such literary work. For further works in

Blin and on Blin, visit the Blin Language Forum, www.daberi.org

[2] In addition to many other entries, published work in Blin include Tekie Albekit (2007), ብሊና ድግም ሕያይቱዲ እንቍርቍራዲ Blin Animal Fables and Riddles. Affa Gebre (2005), ታና Tana (Collected Songs and poems). Hailemariam Ghebre, Abba (2010) ድግምየ ድግም: ኤሶብር ድግም Digim Ye digim: Aesop’s Fables by Wiliam Palme (Translation).

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)