Eritrea: Asmera Street Chronicles

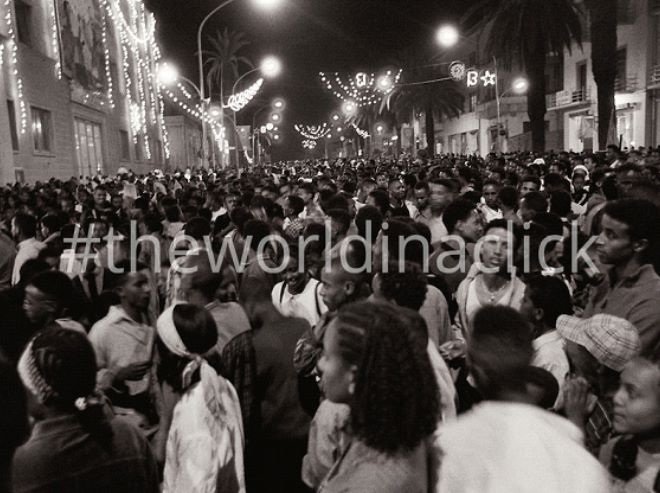

May 24, 2017 is soon approaching. The regime will mobilize tens of thousands of people from the city of Asmera, its metropolitan areas and from all other regions of Eritrea. Marching bands, parading troops and many floating scenes will accompany the multitude of masses, who had been preparing for weeks to conduct a mass rally; a well-rehearsed ceremony, which North Korea had once lent its service. Open air concert will be the finale. The event is the 26th anniversary of the victory of the thirty-year war resulting in the complete loss of sovereignty of Ethiopia over Eritrea.

The inauguration

The venue is Liberation Avenue; formerly knowns as Via Mussolini during Italian Fascist period. As is the custom, the avenue will be full of Eritreans. It is a new phenomenon.

In 1941, when the Allied troops advanced from Keren and Massawa and arrived in Asmera; there was probably no trace of an Eritrean; let alone a crowd. The black and white photograph at the top of the page has captured it. Caution: the swarthy and hat-wearing characters from possibly south Italy should not be confused for the locals.

If a complete stranger to the landscape and its history was asked to describe the scene in the photograph, he/she may think; it was in Europe. A crowd of white people on a side-walk are staring at soldiers in an armored vehicle. The crowd doesn’t appear either to be either jubilant or frightened, but curious.

The scene is however in Asmera, the Fascist town speedily built before the invasion of Ethiopia, in 1935. The race of the crowd, the wide road graced with trees in the vicinity may have deceived the senses of the stranger.

The stranger can’t be blamed for his mistake. It certainly looks like a rendezvous of people, who belong to a white race. The culprit is the Eritrean person, or crowd. In this historic event of early Second World War, which decided the fate of Italy, the Eritrean subject appears to be completely absent at the bend of the street. What explains this spectacle?

Primarily, downtown Asmera, and some other areas were off-limits to the indigenous inhabitants; a policy strictly enforced by the Fascist authorities. With the exception of people, who serve the white settlers as clerks, maids and native soldiers; the large majority of the local people were forbidden to loiter in the zone. In other words, there was no sense of belongingness. The adult population, therefore, made itself scarce from the forbidden district; it didn’t want to intrude into the space designated as a “place in the sun” for the Italians. It perhaps felt, the Allied troops “didn’t” do it for them. [1]

What explains then, the obsession and the fanaticism of “belongingness” to this street-scape; which has been observed during the last quarter of a century, as indicated in the beginning of the story? The sense of “belonging” to the city of modern day Eritrean, which is equally illusory. The sense of new found “identity” of the descendants of the people, who chose to be invisible from this landmark and other locations of the city? What explains the assertion: “Asmara is what we have fought for” [2] by the veterans of the war against Ethiopia?

Bizarre as it may seem, this writer ventures to assert this: among the highlanders a generation or so, with little or no exposure to Apartheid type rule, and scant knowledge of governing or running an economy; mistook all the infrastructure and factories left by the Fascist power, a result of a war economy (sustained by the injection of huge amount of money from Europe) as home grown, or organic. This big misconception further led them to embark on a long protracted war for thirty years, and its resultant war economy to the present day. True to their nature, the African elite immersed the country into another war in Ethiopia in 1998. War economy, war culture and drumbeats have become a permanent feature of the land. Asmara street demonstrates it.

After the inauguration

The pattern is always the same. Having cleverly used the festive-looking- crowd as a prop for a few days; the regime doesn’t sleep long enough, until it empties the youthful population, again. In its sleeve is always the practice of corralling the youth and even the middle-aged out of the city and into the wilderness. In the aftermath of the annual celebrated festivals, the city looks sad and lonely.

The lot of the ordinary modern Eritrean resembles one of his ancestors’ during the dawn of the Second World War: oppressed, serf-like, and displaced and in exile with the following distinction: “his/her” city of Asmera appears forlorn, empty, crumbling and needing a fresh paint.

Ironically, the search for a “place in the sun”; this time, under the modern day indigenous “liberators”; looks steady and enduring. The “liberators” just like the Fascist police have kept Asmera for a certain local elite; resulting in the city’s appearance as “quiet and orderly.” They are too obsessed with cleanliness; a legacy of the Fascist Municipal administration, which dreaded the spread of disease, vagrancy, and crime from the ghettos around the city. They not only violently forbid squatter houses but destroy sturdy houses in the hundreds. Their pride doesn’t allow a tragedy such as the death of around 113 people in the huge garbage landslide that happened in Addis Ababa, recently.

The regime supporters have lately been maligning the Ethiopian authorities for the death of the squatters, whose houses (built on top of a landfill) collapsed. They forget to admit that the authorities in Asmera have been a menace to squatters and that the masses in Asmera are too poor to dispose of anything as a trash. In their eagerness to keep the city as a picture perfect European district, the authorities have hounded out the ubiquitous street vendors, shoe shiners, and beggars, which the rest of Africa still tolerates. Not surprisingly, the city is unlike the vibrant and full of life cities in Africa. The photograph above is a good evidence.

The avenue isn’t a designated vehicle-free area, nor was its picture taken at night. It is rather stark daytime; this doesn’t seem to bother the regimes and its diaspora supporters. The opposition, in the diaspora, on the other hand, had been dreaming for a repeat of some kind of an “Arab Street”, like the one during the heyday of the so-called Arab Spring. This opposition failed to see the almost complete absence of the youth, or the demographic bulge, which actively fought the authoritarian Arab regimes in Tunisia, Egypt, Syria, and Libya from the street. It accused the regime for enforcing a news blackout of the unrest in the Arab world; failing to discern that the regime had already exiled the youth to the wilderness.

In the meanwhile, the desperate Asmarino hasn’t remained passive. Instead, it has earned the reputation of being the trailblazer for a place in the wealthy, but cold northern hemisphere. The Asmarino doesn’t consider the city as a habitat for him anymore, despite the regime’s and some foreign art deco enthusiasts’ relentless lobbying, to have many of the buildings recognized as a Cultural Heritage by the UNESCO. Inflicted with the “mal d’ Europa” (nostalgia) disease forced by repression and globalization, the subject has made himself/herself invisible; reversing the Italian settlers’ journey of the last century.

The journey in search of a “place in the sun” by the Italian settlers, during the early half of the last century, has been reversed by Africans from Asmera and the rest of Eritrea. They embark on the trek to Italy and the rest of Europe in quest of the real “dolce vita”, not the promised them by the “liberators.” The eerie resemblance to the “circular journey” from Asmera to Sahel as depicted by Yosief Ghebrehiwet, may not escape the reader, but with this difference: the passengers in the “ship of fools” heading south were white Europeans and those aiming for the north, Africans.

References

[1] Wrong, Michela, I Didn’t Do It For You: How the World Betrayed a Small African Nation.

[2] Fuller, Mia, Italy’s colonial futures: Colonial Inertia and Post-colonial Capital in Eritrea.

[3] BBC, Ethiopia rubbish dump landslide: search for survivors, March 13, 2017.

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)