Eritrea: from colonialism to independence in photography

It is remarkable is quite how well the history of Eritrea was captured in early photography. Eritrea’s colonial masters were keen to celebrate their successes via photos. These are from my collection.

For the Italians the use of images had been an important element of the Risorgimento, with Garibaldi’s campaigns photographed and distributed by popular carte de visite. The British too had an appetite for colonial photography, both to illustrate the extent of their imperial conquests and to capture the ‘ways of the native.’

My earliest photograph dates from 1868. Britain, furious that the Ethiopian Emperor Tewodros II imprisoned several missionaries and two representatives of the British government, sent a vast army to release them. Some 13,000 British and Indian troops arrived from Bombay on 280 vessels they landed at Zula on Eritrean coast 48 km south of Massawa.

Here their camp is seen preparing to attack the Emperor inside Ethiopia itself.

Having defeated and killed the Emperor and looted his palace, the British departed.

However London was worried about expanding French influence in Africa, and chose to encourage Italy to take Massawa. The Italians were ideal candidates to play this role: they already had an Eritrean foothold.

In 1896 Italy decided to use Eritrea as a base from which to attack Ethiopia itself. This was a mistake. In a rare reversal of the normal run of clashes between European and African nations, the Italians were decisively defeated at the battle of Adua. The defeat was a major blow to the Italians, who lost thousands of troops killed and captured.

With the rise of fascism under Mussolini, Italy was determined to avenge this loss of face and extend its presence in the Horn of Africa. In October 1935 Italy invaded Ethiopia from the territory it controlled in Eritrea.

This photograph shows the moment the invasion took place.

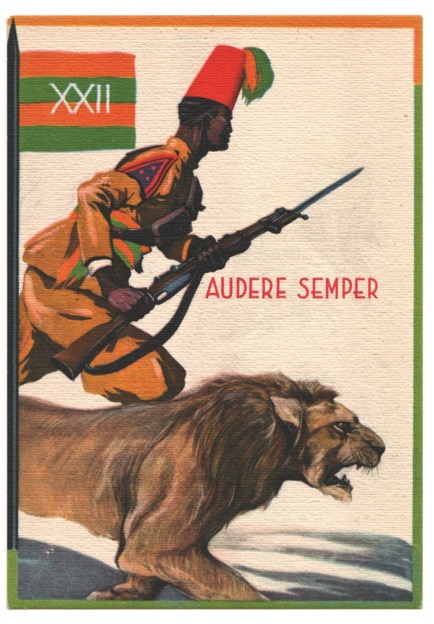

What is remarkable about the occupation of Eritrea and the invasion of Ethiopia is that the Italians were extremely proud of the fact that they had raised thousands of Eritrean local troops – or ‘askaris’.

These were formed into individual battalions and each had a postcard made to celebrate its achievements. The postcards portray the Eritreans in a distinctly heroic light and there was certainly no attempt to denigrate the ‘askaris’ on whom the Italians relied.

Despite the League of Nation’s condemnation of the Italian action aggression it was not until the outbreak of the Second World War that the world took a decisive stand against their aggression.

Here Ethiopian forces are marching out of the town of Harar to face the Italian advance.

Using tanks, aerial bombardment and nerve gas the Italians captured Addis Ababa on 5 May 1936. The emperor had left for exile in Britain but Ethiopian guerrilla forces continued the fight.

By 1941 Emperor Haile Selassie had been returned to his throne by a combined force of British, South African, Indian and Sudanese troops fighting alongside Ethiopian patriots.

This photograph shows South African forces – the Transvaal Scottish – entering Addis Ababa.

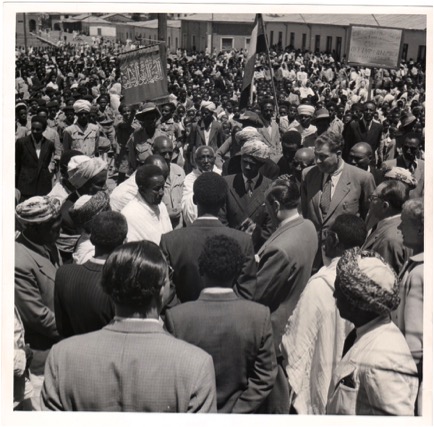

When the war was over Britain was uncertain quite what to do with Eritrea, which had been run by a temporary British Military Administration after it was captured in 1941. In 1949 London referred the matter to the United Nations, which sent a mission to investigate quite what should happen to Eritrea.

Here they are seen meeting the local population in Asmara.

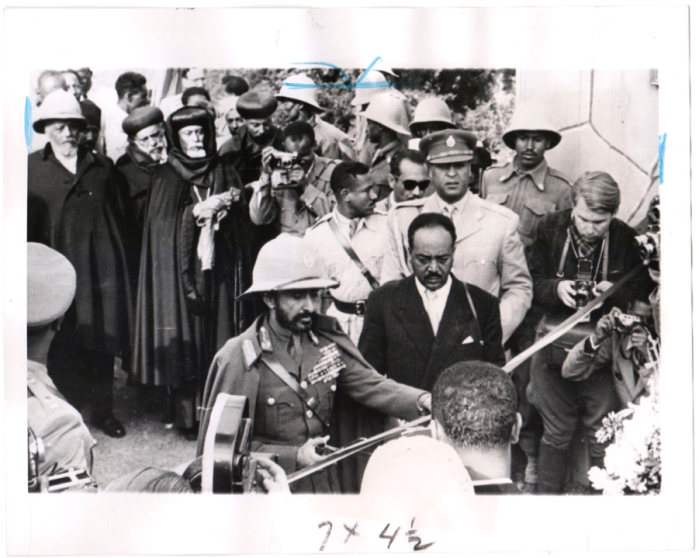

In 1952 the United Nations finally to decide that the territory should be federated with Ethiopia.

Here Emperor Haile Selassie is shown on 3 October 1952, using ‘golden scissors to sever tape on boundary between his country and Eritrea Oct. 3, marking federation of Eritrea and Ethiopia,’ as the caption reads.

There matters might have rested.

However, the Emperor’s absolutist rule alienated the Eritrean population by a series of decrees. These included outlawing the teaching of Eritrean languages, replacing them with Amharic (the official language of the empire), dismantling industries and removing them to Addis Ababa and repressing the trade union movement and political parties allowed under the British military administration. In 1962 the Federation was ended and Eritrea became a province of the Empire.

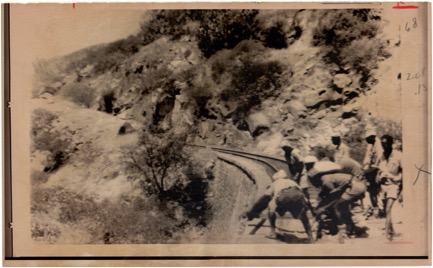

By the early 1960’s this repression was being met by armed resistance from the Eritrean Liberation Front. The ELF, drawn mainly from the Muslim population of the lowlands, attacked key installations.

Here they are show blowing up the railway line in December 1970.

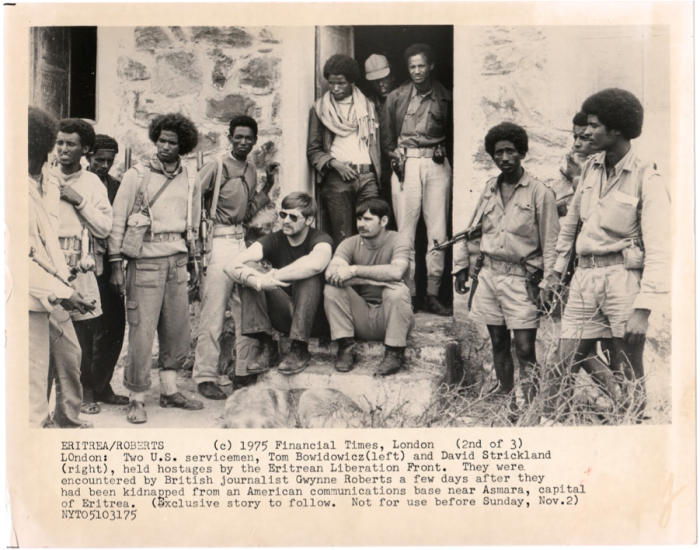

In this period the ELF took western hostages, as bargaining tools against Ethiopia.

Most – including these two Americans – were well treated and released in January 1976.

By 1981 the ELF had been forced out of Eritrea by the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) in a bloody civil war. At the same time the war against Ethiopian continued.

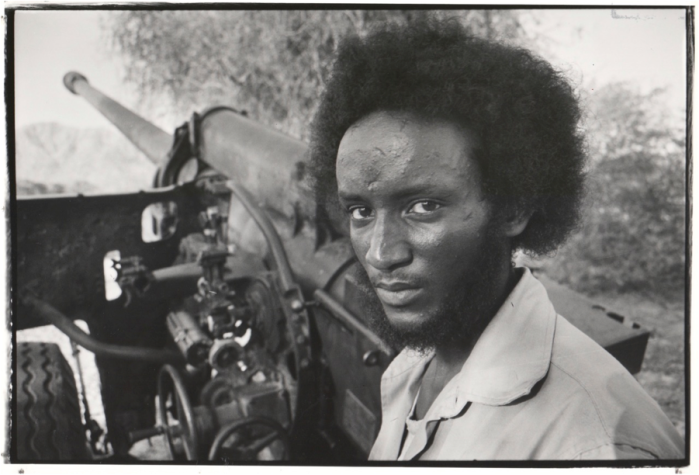

By June 1990 the EPLF took the port of Massawa and this photograph is captioned: ‘A EPLF rebel stands in front of a captured Soviet-made cannon used in the taking of the port of Massawa. The EPLF says it has an enormous supply of weapons, all Soviet-made and captured from the Ethiopians.’

With Massawa having fallen the Ethiopians used their air superiority to bomb the city. Here civilians are seen in June 1990 taking refuge in a culvert to escape the attacks.

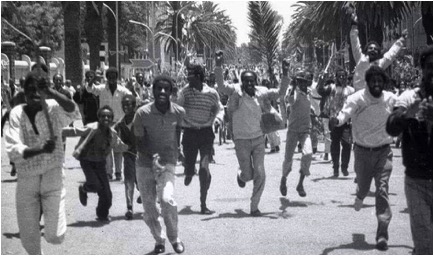

Finally, after a war of liberation lasting three decades, the EPLF entered Asmara on 24 May 1991. Greeted with jubilation, many of the fighters were seeing their capital for the first time.

The EPLF decided against declaring immediate independence, preferring to have the UN oversee an independence referendum in 1993. The result was 99.83% in favour, with a 98.5% turnout. Independence was declared on 27 April 1993. Eritrea had emerged as a fully fledged member of the UN and the Organisation of African Unity.

It was the culmination of three decades of sacrifice – some moments of which had been captured in the photographs of the journalists and photo-reporters who had visited the country.

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)